-----Register

-----Readed_count

-----Update_order

한국 명화감상

세계 명화감상

그리스.로마신화

Mobile Menu, Mobile W-paintings, Cyber World Tour,

한국역사부도,

세계역사부도,

역사년표

NEW

RENEWAL

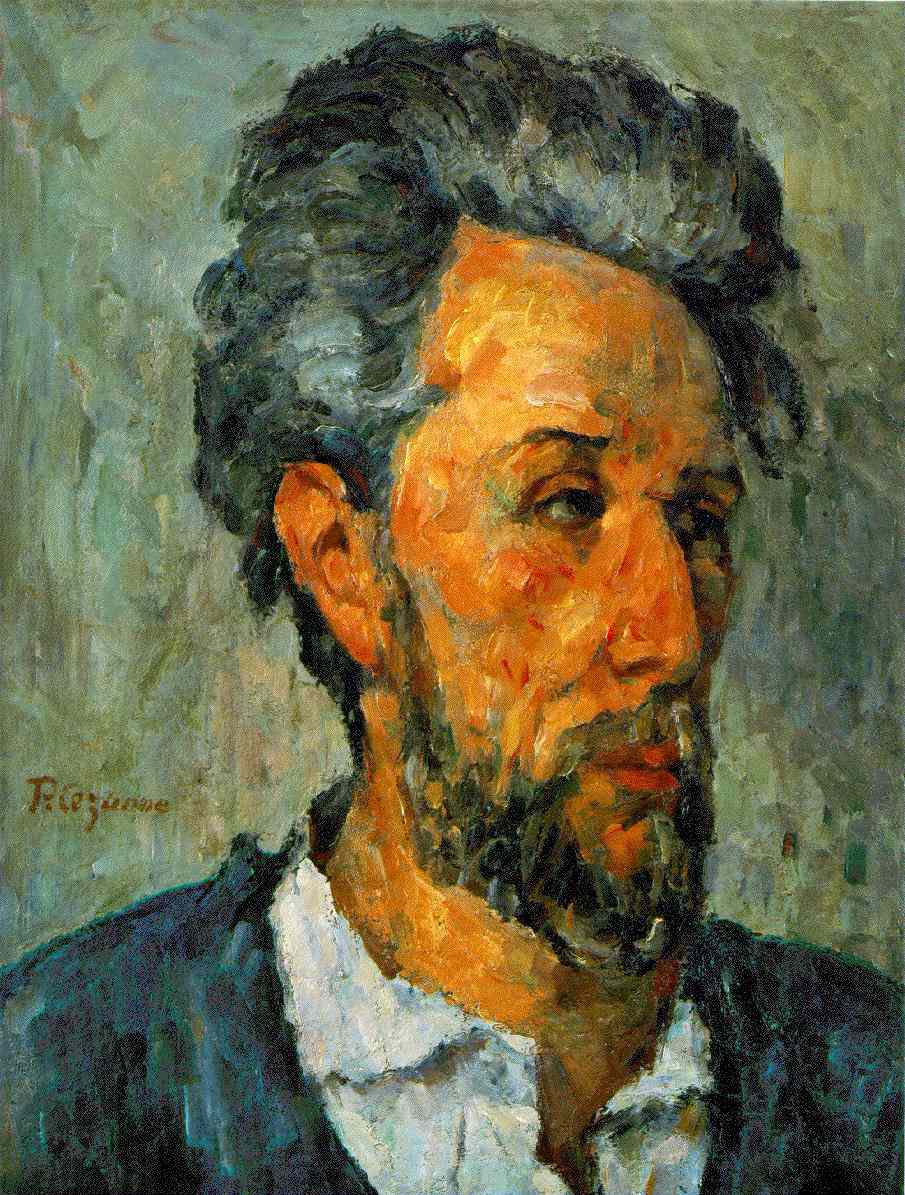

1875 Oil on canvas 18 1/8 x 14 1/8 inCollection Lord Victor Rothschild, Cambridge, EnglandCezanne, Paul

Self-Portraits

Text from Steven Platzman, introduction to "Cezanne: The Self-Portraits"

"Look at a self-portrait by Cezanne. What do you see? Is it a meaningful portal to the artist's persona, in accordance with the western tradition of this august genre? Is there information beyond the wonder of the style? With his discrete strokes, like so many transparent and opaque tiles, the mature Cezanne rethought the entire pictorial transcription of material structure. As he told his friend and fellow artist Emile Bernard, "to read nature is to see her, underneath the veil of interpretation, as colored taches following one another according to a law of harmony." But what of himself? Did he find his own essence conveyable by no more than an assemblage of strokes of fastidiously chosen colors, such as he used to rebuild an observed arrangement on a table or a prospect of a landscape? Does a Cezanne self-portrait tell of feelings and emotions? Or do those colored strokes, which the artist found to be the visual essence of the natural world, provide, in effect, an obscuring "veil of interpretation" that impedes a meaningful look at the man behind one of the greatest revolutions in the history of art?

"We approach Cezanne knowing that his art-historical position is exquisitely pivotal, that his mature style is part of the canon of early modernism, and that his iconic images of apples and rocky outcroppings tend to be forms forever associated with his uniquely analytic touch. Against this venerable legacy, the corpus of self-portraits may appear to rest somewhat uncomfortably. One expects more of a self-portrait from a master than color and structural analysis. After all, masterful portraiture calls for a different set of analytic skills than does interpreting a grouping of objects on a table or a passage of landscape. Did Cezanne achieve something significant in the tradition of self-examination in pencil and paint?

"Writers seeking a definition of the painted self-portrait have generally preferred the verb "construct" rather than "record." Every artist confronting him or herself is faced with questions far more profound than whether or not a likeness has been achieved. Historically at least, a correct or reasonably accurate transcription of form was a prerequisite, but transcendent and memorable self-portraits have always provided more than topography. In twentieth-century and even twenty-first-century parlance, self-portraiture is said to tell of the psyche, of the sense of self-worth, of how the painter or draftsperson wished to be perceived. To transcend the bounds of mere likeness requires new construction, construction by the creator of the portrait. "Constructing" implies calculation, choices and manipulation. It is the perfect verb to describe everything that Cezanne does.

"But if Cezanne constructs his self-image through the same signature style employed to fashion his still lifes and landscapes, it is fair to ask whether that style was adequate to convey what one seeks in a successful self-portrait aside from the likeness of the artist. Cezanne's style, instantly recognizable and notoriously analytical, is ideal for interpreting physical structure. But is it effective at conveying emotional information? A painterly report on the persona as opposed to the mere depiction ofits corporeal vessel appears a tall order for a style largely in bondage to color in nature, to rephrase John Gage. More to the point is whether that persona is resistant to his painterly method, or is it somehow expressed in his revolutionary application of paint and use of color? Perhaps what we may read of the artist's inner self is provided not by the structural characteristics that easily describe Cezanne's celebrated style but by the suggestive qualities of that style as it is employed to describe and distill the artist's physiognomy. One might inquire further whether the painter's character and ambition are perhaps to be deciphered from some arcane confabulation between his choices of pose and the faceting of his physiognomy? Simply put, we ask whether we can see through the wonderful barrier that is Cezanne's brilliant surface, and what is there to understand if we do?...

"...Cezanne owes an ultimate debt to the greatest German artist of the sixteenth century, Albrecht Dürer (1471-1528), for the Northern Renaissance master, in addition to his many other achievements, may be considered a pioneer of the independent self-portrait - that is, of the image of the artist created as an autonomous work of art.

"Through Dürer the sub-genre of self-portraiture gained its independence from its dominant counterpart, portraiture. Dürer first accomplished this art-historical milestone in the Self-Portrait of 1493, now in the Louvre. Here, the handsome young man, in the midst of marriage negotiations, poses as any young, middle-class Nuremberg burgher might in a conventional wedding portrait, holding a flower symbolizing luck in love. Despite the painting's simplistic integrity, there is an air of refinement pervading the image. This elegance faintly reveals itself in Dürer's bearing and finds poignant expression in the graceful description of the artist's hands, the physical source of his artistic genius.

"Not only was Dürer a progenitor of the autonomous self-portrait, but, more than any of his predecessors, he assigned his own self-image a significant place in his oeuvre, employing it as a tool of personal exploration as well as a public statement of his worldly ambitions. Just as the 1493 Self-Portrait is remarkable for its composition, the Self-Portrait of l498, now in the Prado, is astonishing for its audacious display of social ambition. Having achieved material success through his recent publication of woodcuts, and having experienced the world through his travels, the young man depicts himself in a station far above his modest birthright. He is outfitted in cosmopolitan and ostentatious garb, including expensive doeskin gloves, a Nuremberg specialty.

"Such an arrogant presentation was reserved for the social elite, but in this case Dürer has purposely elevated himself, self-consciously stressing his own commitment to fashion as well as his cultural refinement. Just as the painting's execution reflects an Italianate influence - use of subtle chiaroscuro, steadfast architectonic composition, and the insertion of an atmospheric passage of landscape - its philosophical underpinnings also belie a humanistic conception derived from Italian Renaissance thought. It was, in fact, from his sojourn in Italy that Dürer acquired social ambition and the notion of the artist as a member of an elite and perhaps even sovereign class - an alien idea in his native Germany. Hence his famous remark in a letter of 1506 from Venice to his friend Willibald Pirckheimer: "Here I am a gentleman, while at home I am a parasite."

"In another self-portrayal of the same period, now in the Altere Pinakothek in Munich, the staring, sober, Christ-like countenance of the artist is centered at the top of a pyramid established by the slopes of curls that cascade from his head. The artist has constructed an image that inspires both respect and sympathy. If this is not a holy man, it is a man on a holy mission. Rather than a soulful complaint, however, this remarkable self-portrait, like the remark to Pirckheimer, shows a sensitivity to the artist's lack of standing and divulges a tenacious drive to renegotiate the perceived value and position of both the maker and object...

"...no seventeenth-century master devoted more effort to self-examination than did Rembrandt van Rijn (1606-69). Indeed, there have been few artists in history who have so sustained an interest in making pictures of themselves throughout the different phases of their careers. Cezanne is one of those.

"From youth to old age, Rembrandt scrutinized himself before the mirror, painting, etching, and drawing his changing physique and physiognomy as well as the varying psychological states that reflected the fluctuating fortunes of his fife. Like Cezanne more than two centuries later, Rembrandt employed the self-portrait as part of an effort to fashion the self, a self that took on multiple forms as the Dutch master progressed from youth to old age.

"Beginning in 1621, Rembrandt embarked on a new trajectory and began to fashion different identities in independent self-portraits. It was as if he was searching for a fit - a persona that would best align with his propensities at the time. Like a voting man choosing clothes for his first outing into town, Rembrandt tried to portray a suitable identity before his departure from Leiden to Amsterdam in 1631. Thus, in the brief period between 1629 and 1631, the ambitious voting artist appeared in his self-portraits as a melancholic youth, a gentleman, and a military officer. The gallant military figure seems to have especially appealed to the young Rembrandt, for he portrayed himself on numerous occasions (well into the 1630s) wearing armor, usually a gorget. Prior to the commission of The Nightwatch (1642), however, Rembrandt maintained no connection with the military. As a result, one must assume that his donning of military garb was an attempt at some sort of ideal guise. Armor in Rembrandt's Netherlands possessed patriotic associations, and anyone wearing such gear proclaimed an unspoken allegiance to the fatherland. Apparently, the identity of the artist-patriot seemed most agreeable to the youthful Rembrandt. As he matured, however, armor, patriotism, and all of the glamorous associations of war would lose their general appeal, and other identities would more powerfully attract his unsettled self.

"Thus, while he remained in Amsterdam, Rembrandt turned to less flamboyant expressions of self, flirting with identities ranging from the burjerlick gentleman to the working artist. Most noteworthy for the history of the genre was Rembrandt's journey from the narcissistic self-absorption of his youthful portrayals to the vulnerable self-admission of his late confrontations with his person. In fact, Rembrandt's ability to communicate across the centuries is undoubtedly due to the perceived honesty of his self-examination. His appeal is perhaps to be found in his ability to paint "between the lines" to give the viewer the tools to see through the very self-images he constructs. Thus when he poses one senses the artifice, and when he reveals one is smitten with the sincerity of the disclosure...

"The reading of self-portraits raises numerous issues which must be confronted before Cezanne's self-representations can be considered either as a group - an autobiography of his life - or as individual works of art. As the discussion of both Durer's and Rembrandt's self-portraits indicate, the images can contain an infinite variety of meanings revealing, for example, social and professional ambitious or personal thoughts on the creation of art. In effect, the self-image can stand as a statement of self-analysis, the conflated dialogue between the painting hand and the painting head reflecting the richness and ambiguity inherent in any profound conversation. A self-portrait, however, also can be read as a superficial representation of the artist's physical attributes - the so-called likeness. Here, the artist finds his own body a convenient subject of observation, eliminating the need for a model. In the past, Cezanne's self-portraits have been, for the most part, treated as purely structural analyses, marking the changing physiognomy of the artist as he developed from passionate youth to meditative old age, from underappreciated avant-garde painter to the father of modern art. They tend to pepper monographs on the artist, sometimes standing at the head of each chapter like totemic reminders: here is the great Cezanne, at age thirty-three just before he entered his Impressionistic phase. Or, here he is at thirty-seven as he moves into his constructive phase, employing his parallel-hatch brushstroke. Shortly he will produce the great canvases that will influence the likes of Picasso with their geometric fracturing of surface planes.

"The reasons for the failure of art history to reflect more deeply on these images are manifold, but the various social and historical factors which influenced the course of academic criticism must be among the first causes cited. Fundamentally, however, it is the simplicity of the images which makes then so difficult to penetrate. For the most part, the paintings and drawings are exceedingly restrained in their presentation of self, there are few grand gestures or complex poses to contend with, and they may even have an air of repetitious banality on first encounter. Cezanne tends always to sit in a three-quarter or bust-length pose facing the spectator. These hieratic formulations create extreme difficulties for those who are writing art history. What can one say about such outwardly simple renditions? Well, the artist is younger here or older there, and let us move on to what we know the artist painted, for he is the master of the modern still life and the heir to the great tradition of classical landscape painting.

"And it is this mythology - this story of the painter's relationship to modernism and the twentieth century that has relegated the self-portraits (and for that matter, his portraits) to the art-historical dustbin. For post-World War II art criticism, the figure was an anathema, part of a tradition that was "thankfully" discarded for something more relevant, like abstraction - flat planes of color that merge with the canvas reinforcing what is singular to painting. How could the father of modern art, the wellspring of modernism, be a portrait painter? Rather than dealing with these images, they were simply pushed aside as distracting efforts of the artist destined for greater things. Certainly, a portrait of himself could not compete with a flickering image of Mont Sainte-Victoire or the impossibly arranged fruit and jars of a permanently shifting still life.

"When one considers that the figure in the history of art was always of the highest importance and that still life and landscape were the lowliest of genres, this twentieth-century slight seems rather absurd. But the rejection of the figure was part of the twentieth-century's evolving rejection of the medium of painting itself. Have we not heard on more than one occasion that painting is dead? With the reduction of painting to nothing but the canvas itself, and the rising popularity of performance and video art, it truly seemed for a brief moment that painting indeed may have been in its final death throes as part of an epochal change.

"Yet, at the beginning of the twenty-first century, the cry for the elimination of the subject and the destruction of painting has diminished. For some time now, being an avant-garde painter has not required a commitment to abstraction. It has been possible to return to the figure and still be considered relevant to the age, Just as artists are able to express themselves in a figurative language, so may art historians. And to be a serious art historian one does not need to be following in the footsteps of formalism laid down by Clement Greenberg. Despite his important contributions to the history of art, his preeminent position stifled debate just as a monopoly stifles competitive commerce. This new tolerance of diversity allows us to go back and reconsider that which was deemed out of step with the drive to modernist abstraction. It permits a reconsideration of figurative art and in particular the self-portrait. With our eyes refocused, Cezanne becomes much more than a painter of still lifes and landscapes - he becomes a complex personality whose attention was drawn time and time again to the figure, and more importantly for this discussion, to his own physiognomy."

한국 Korea Tour in Subkorea.com Road, Islands, Mountains, Tour Place, Beach, Festival, University, Golf Course, Stadium, History Place, Natural Monument, Paintings, Pottery, K-jokes, 중국 China Tour in Subkorea.com History, Idioms, UNESCO Heritage, Tour Place, Baduk, Golf Course, Stadium, University, J-Cartoons, 일본 Japan Tour in Subkorea.com Tour Place, Baduk, Golf Course, Stadium, University, History, Idioms, UNESCO Heritage, E-jokes, 인도 India Tour in Subkorea.com

History,

UNESCO Heritage, Tour Place,

Golf Course,

Stadium,

University, Paintings,

History,

UNESCO Heritage, Tour Place,

Golf Course,

Stadium,

University, Paintings,

|

|

조회 수 | 추천 수 | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

공지

World Museums Report & Map

|

33933 | |

|

공지 재미있는 미술스토리와 경매이야기, 그리고 작품감상 [1] | 24557 | |

|

|||